When considering clinical data collected from sites, what is the relationship between these two factors?

- Quantity: the number of patients enrolled by the site

- Quality: the rate of data issues per enrolled patient

Obviously, this has serious implications for those of us in the business of accelerating clinical trials. If getting studies done faster comes at the expense of clinical data quality, then the value of the entire enterprise is called into question. As regulatory authorities take an increasingly skeptical attitude towards missing, inconsistent, and inaccurate data, we must strive to make data collection better, and absolutely cannot afford to risk making it worse.

As a result, we've started to look closely at a variety of data quality metrics to understand how they relate to the pace of patient recruitment. The results, while still preliminary, are encouraging.

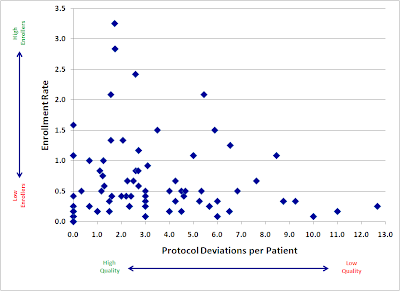

Here is a plot of a large, recently-completed trial. Each point represents an individual research site, mapped by both speed (enrollment rate) and quality (protocol deviations). If faster enrolling caused data quality problems, we would expect to see a cluster of sites in the upper right quadrant (lots of patients, lots of deviations).

Instead, we see almost the opposite. Our sites with the fastest accrual produced, in general, higher quality data. Slow sites had a large variance, with not much relation to quality: some did well, but some of the worst offenders were among the slowest enrollers.

There are probably a number of reasons for this trend. I believe the two major factors at work here are:

- Focus. Having more patients in a particular study gives sites a powerful incentive to focus more time and effort into the conduct of that study.

- Practice. We get better at most things through practice and repetition. Enrolling more patients may help our site staff develop a much greater mastery of the study protocol.

We will continue to explore the relationship between enrollment and various quality metrics, and I hope to be able to share more soon.